what caused cotton and tobacco prices to fall 8-6.2

iii.three Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium

Learning Objectives

- Use demand and supply to explain how equilibrium price and quantity are determined in a market.

- Understand the concepts of surpluses and shortages and the pressures on cost they generate.

- Explain the impact of a alter in need or supply on equilibrium price and quantity.

- Explain how the circular menses model provides an overview of demand and supply in product and cistron markets and how the model suggests ways in which these markets are linked.

In this section we combine the demand and supply curves nosotros take but studied into a new model. The model of need and supply uses need and supply curves to explain the determination of cost and quantity in a market.

The Determination of Price and Quantity

The logic of the model of demand and supply is simple. The demand curve shows the quantities of a particular good or service that buyers will be willing and able to purchase at each toll during a specified menses. The supply curve shows the quantities that sellers will offer for sale at each price during that aforementioned period. By putting the two curves together, we should be able to find a price at which the quantity buyers are willing and able to purchase equals the quantity sellers will offer for sale.

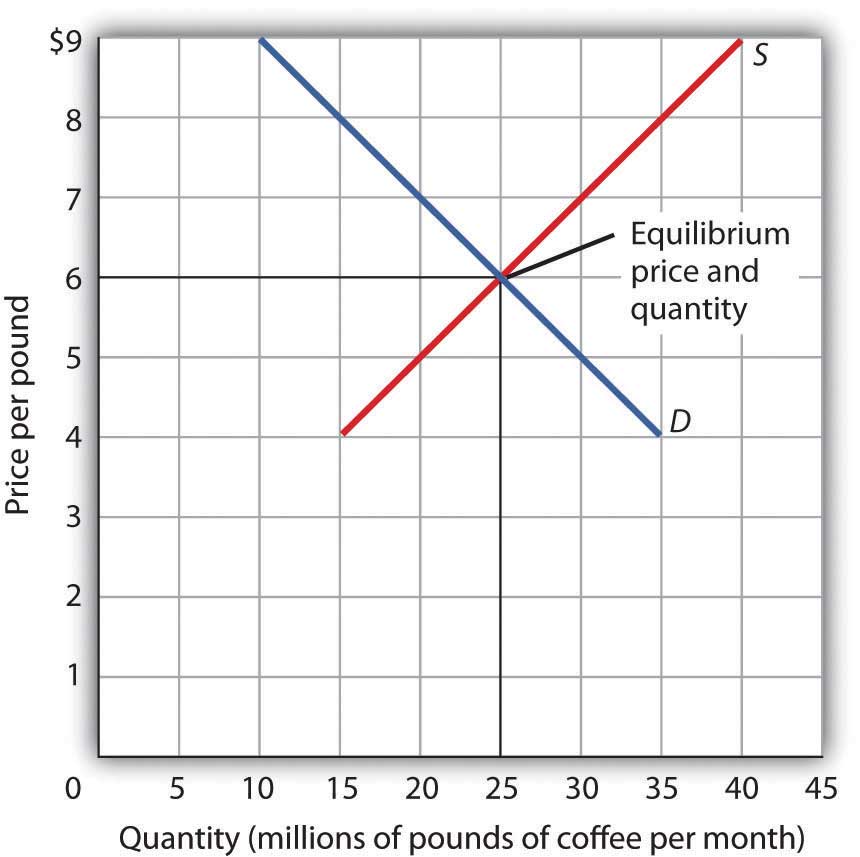

Figure 3.7 "The Determination of Equilibrium Price and Quantity" combines the demand and supply information introduced in Figure three.1 "A Demand Schedule and a Demand Bend" and Figure iii.4 "A Supply Schedule and a Supply Curve". Notice that the two curves intersect at a price of $six per pound—at this price the quantities demanded and supplied are equal. Buyers want to purchase, and sellers are willing to offer for sale, 25 million pounds of coffee per calendar month. The market for coffee is in equilibrium. Unless the demand or supply curve shifts, in that location volition be no trend for price to alter. The equilibrium toll in whatsoever market is the price at which quantity demanded equals quantity supplied. The equilibrium toll in the market for coffee is thus $6 per pound. The equilibrium quantity is the quantity demanded and supplied at the equilibrium price. At a price to a higher place the equilibrium, there is a natural tendency for the toll to fall. At a cost below the equilibrium, there is a tendency for the toll to rise.

Effigy 3.7 The Determination of Equilibrium Price and Quantity

When we combine the demand and supply curves for a practiced in a single graph, the point at which they intersect identifies the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity. Here, the equilibrium toll is $6 per pound. Consumers demand, and suppliers supply, 25 million pounds of java per calendar month at this price.

With an upwardly-sloping supply bend and a downward-sloping demand curve, there is only a unmarried cost at which the ii curves intersect. This means there is only i price at which equilibrium is achieved. It follows that at any price other than the equilibrium price, the market volition not be in equilibrium. We next examine what happens at prices other than the equilibrium price.

Surpluses

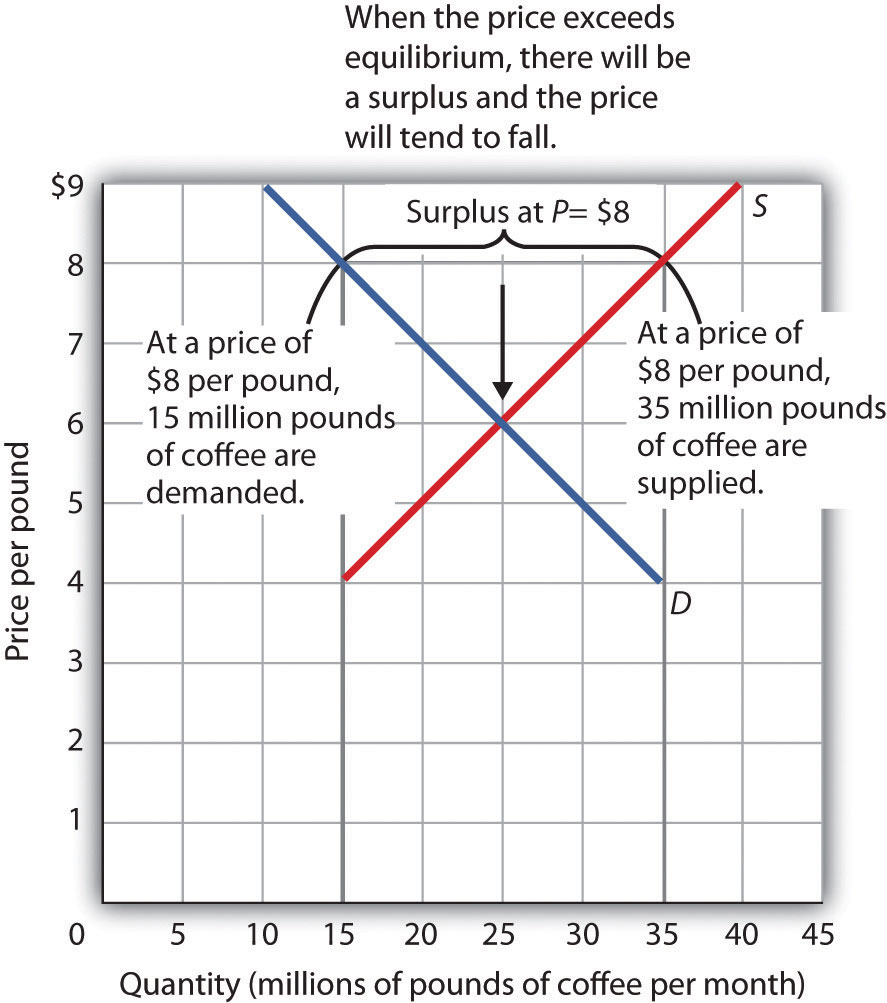

Figure 3.8 "A Surplus in the Market for Coffee" shows the aforementioned demand and supply curves we have only examined, but this time the initial price is $eight per pound of coffee. Because nosotros no longer have a balance betwixt quantity demanded and quantity supplied, this price is not the equilibrium cost. At a price of $viii, we read over to the demand bend to determine the quantity of coffee consumers volition be willing to purchase—15 million pounds per month. The supply curve tells us what sellers will offer for auction—35 1000000 pounds per calendar month. The deviation, 20 million pounds of coffee per calendar month, is called a surplus. More generally, a surplus is the amount past which the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the current price. There is, of grade, no surplus at the equilibrium price; a surplus occurs merely if the current toll exceeds the equilibrium toll.

Figure 3.8 A Surplus in the Market for Coffee

At a cost of $eight, the quantity supplied is 35 million pounds of coffee per month and the quantity demanded is 15 meg pounds per month; there is a surplus of 20 million pounds of coffee per month. Given a surplus, the price will autumn chop-chop toward the equilibrium level of $vi.

A surplus in the market place for coffee will not last long. With unsold java on the market, sellers will begin to reduce their prices to clear out unsold coffee. Equally the price of coffee begins to fall, the quantity of coffee supplied begins to decline. At the same time, the quantity of java demanded begins to ascension. Call back that the reduction in quantity supplied is a move along the supply curve—the curve itself does not shift in response to a reduction in cost. Similarly, the increase in quantity demanded is a movement along the demand curve—the need curve does not shift in response to a reduction in price. Cost will continue to fall until information technology reaches its equilibrium level, at which the demand and supply curves intersect. At that point, there will be no trend for price to fall further. In general, surpluses in the marketplace are short-lived. The prices of about goods and services adjust quickly, eliminating the surplus. Afterward on, we will discuss some markets in which adjustment of price to equilibrium may occur only very slowly or not at all.

Shortages

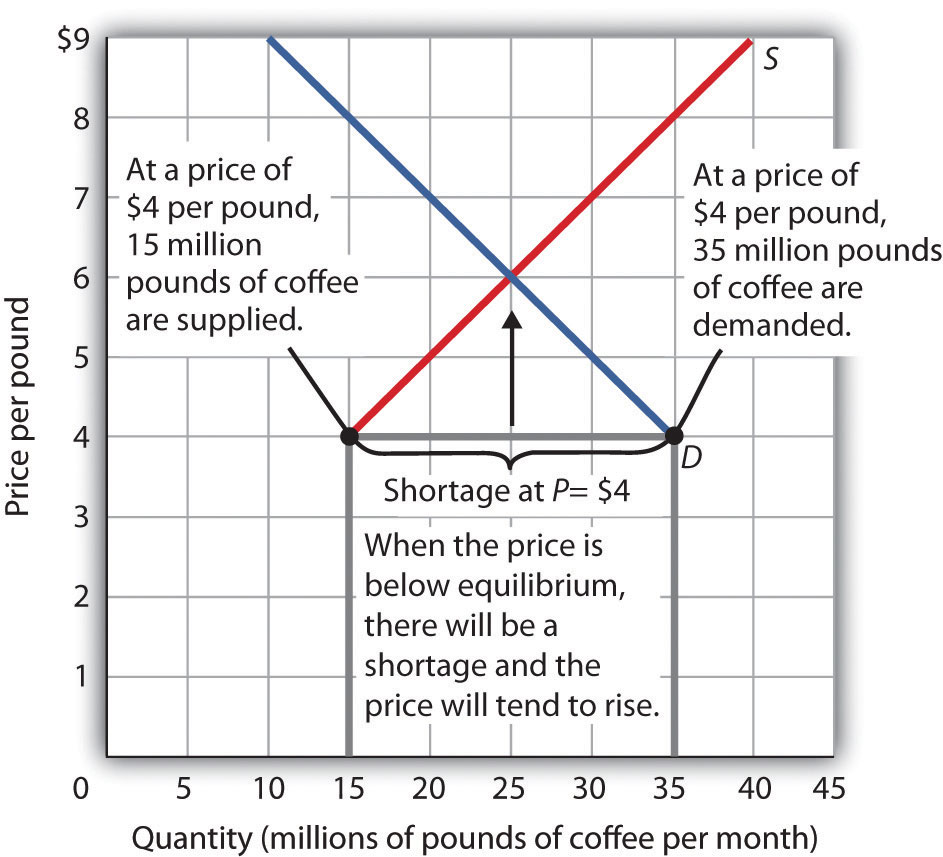

Simply every bit a price above the equilibrium cost will crusade a surplus, a price below equilibrium will cause a shortage. A shortage is the amount by which the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at the electric current price.

Figure 3.9 "A Shortage in the Market for Coffee" shows a shortage in the market place for coffee. Suppose the price is $four per pound. At that price, xv 1000000 pounds of coffee would exist supplied per month, and 35 million pounds would be demanded per month. When more coffee is demanded than supplied, there is a shortage.

Effigy iii.9 A Shortage in the Market for Java

At a price of $iv per pound, the quantity of coffee demanded is 35 million pounds per month and the quantity supplied is fifteen meg pounds per month. The event is a shortage of 20 1000000 pounds of java per month.

In the face of a shortage, sellers are probable to begin to raise their prices. As the toll rises, in that location will be an increase in the quantity supplied (just non a modify in supply) and a reduction in the quantity demanded (but not a change in need) until the equilibrium toll is achieved.

Shifts in Need and Supply

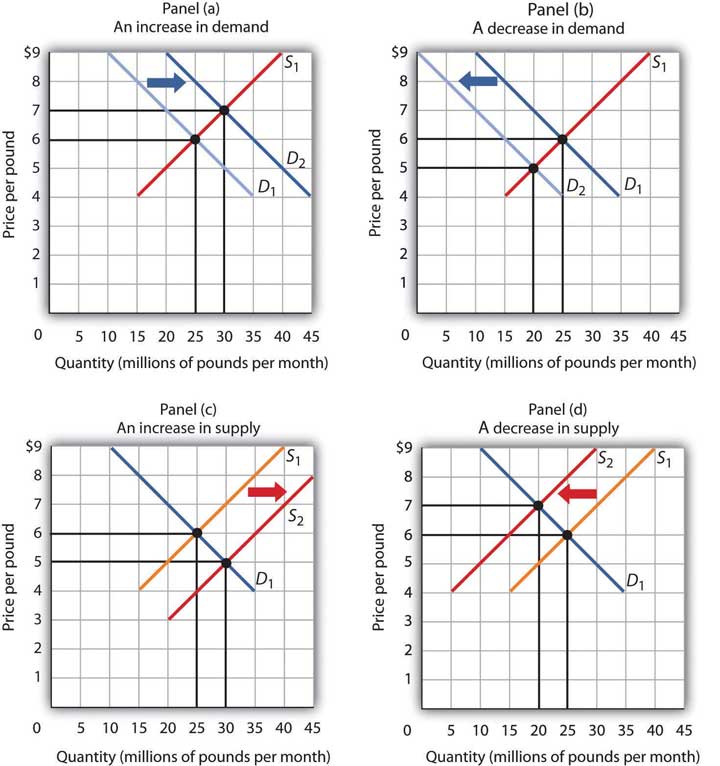

Effigy 3.10 Changes in Demand and Supply

A change in need or in supply changes the equilibrium solution in the model. Panels (a) and (b) show an increase and a subtract in need, respectively; Panels (c) and (d) bear witness an increase and a decrease in supply, respectively.

A modify in one of the variables (shifters) held constant in any model of demand and supply volition create a change in need or supply. A shift in a demand or supply curve changes the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity for a practiced or service. Figure 3.10 "Changes in Demand and Supply" combines the information about changes in the demand and supply of coffee presented in Effigy 3.2 "An Increase in Demand", Figure 3.three "A Reduction in Demand", Effigy 3.5 "An Increase in Supply", and Figure three.6 "A Reduction in Supply" In each case, the original equilibrium price is $six per pound, and the corresponding equilibrium quantity is 25 million pounds of coffee per month. Effigy 3.ten "Changes in Demand and Supply" shows what happens with an increase in need, a reduction in demand, an increase in supply, and a reduction in supply. We so wait at what happens if both curves shift simultaneously. Each of these possibilities is discussed in turn below.

An Increase in Need

An increase in demand for coffee shifts the need curve to the right, every bit shown in Panel (a) of Figure 3.10 "Changes in Demand and Supply". The equilibrium price rises to $vii per pound. As the price rises to the new equilibrium level, the quantity supplied increases to 30 one thousand thousand pounds of coffee per month. Notice that the supply curve does non shift; rather, there is a movement along the supply curve.

Demand shifters that could cause an increase in need include a shift in preferences that leads to greater coffee consumption; a lower price for a complement to coffee, such as doughnuts; a higher price for a substitute for coffee, such every bit tea; an increase in income; and an increment in population. A change in heir-apparent expectations, perhaps due to predictions of bad weather lowering expected yields on coffee plants and increasing future java prices, could also increase current demand.

A Subtract in Demand

Panel (b) of Effigy 3.10 "Changes in Demand and Supply" shows that a decrease in demand shifts the demand curve to the left. The equilibrium price falls to $5 per pound. As the price falls to the new equilibrium level, the quantity supplied decreases to 20 million pounds of coffee per month.

Demand shifters that could reduce the demand for coffee include a shift in preferences that makes people want to consume less coffee; an increase in the price of a complement, such equally doughnuts; a reduction in the price of a substitute, such as tea; a reduction in income; a reduction in population; and a change in buyer expectations that leads people to wait lower prices for java in the future.

An Increment in Supply

An increase in the supply of coffee shifts the supply bend to the right, as shown in Panel (c) of Effigy iii.10 "Changes in Need and Supply". The equilibrium toll falls to $v per pound. As the price falls to the new equilibrium level, the quantity of java demanded increases to 30 million pounds of java per month. Notice that the demand curve does not shift; rather, there is movement along the demand curve.

Possible supply shifters that could increment supply include a reduction in the price of an input such as labor, a pass up in the returns available from alternative uses of the inputs that produce java, an improvement in the technology of coffee production, practiced weather, and an increase in the number of coffee-producing firms.

A Decrease in Supply

Panel (d) of Effigy iii.10 "Changes in Demand and Supply" shows that a subtract in supply shifts the supply curve to the left. The equilibrium price rises to $7 per pound. Equally the toll rises to the new equilibrium level, the quantity demanded decreases to 20 million pounds of java per calendar month.

Possible supply shifters that could reduce supply include an increase in the prices of inputs used in the production of coffee, an increment in the returns available from alternative uses of these inputs, a decline in production because of problems in technology (perchance caused by a brake on pesticides used to protect coffee beans), a reduction in the number of coffee-producing firms, or a natural result, such as excessive rain.

Heads Up!

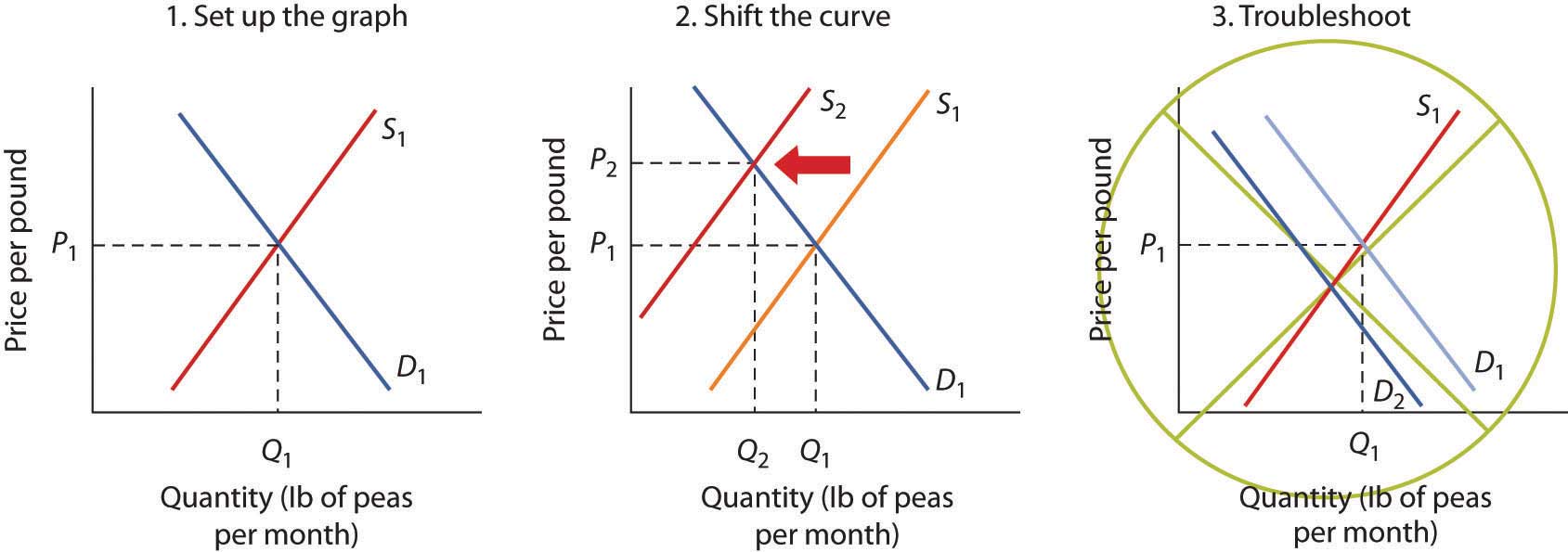

You are likely to be given issues in which y'all will have to shift a demand or supply curve.

Suppose you are told that an invasion of pod-crunching insects has gobbled upward half the ingather of fresh peas, and you are asked to use demand and supply assay to predict what volition happen to the price and quantity of peas demanded and supplied. Here are some suggestions.

Put the quantity of the good you are asked to analyze on the horizontal axis and its price on the vertical axis. Describe a downwardly-sloping line for need and an up-sloping line for supply. The initial equilibrium price is determined by the intersection of the two curves. Characterization the equilibrium solution. You may find it helpful to apply a number for the equilibrium toll instead of the letter "P." Pick a price that seems plausible, say, 79¢ per pound. Practice not worry almost the precise positions of the demand and supply curves; you cannot be expected to know what they are.

Step two can be the most difficult stride; the trouble is to decide which curve to shift. The key is to remember the difference between a change in demand or supply and a alter in quantity demanded or supplied. At each price, enquire yourself whether the given issue would change the quantity demanded. Would the fact that a bug has attacked the pea crop change the quantity demanded at a cost of, say, 79¢ per pound? Clearly not; none of the need shifters have changed. The event would, nonetheless, reduce the quantity supplied at this cost, and the supply bend would shift to the left. At that place is a change in supply and a reduction in the quantity demanded. There is no change in demand.

Next check to see whether the event you have obtained makes sense. The graph in Step 2 makes sense; information technology shows price rise and quantity demanded falling.

It is easy to make a mistake such every bit the 1 shown in the tertiary effigy of this Heads Up! 1 might, for example, reason that when fewer peas are available, fewer volition be demanded, and therefore the demand curve will shift to the left. This suggests the toll of peas will fall—but that does not make sense. If only half every bit many fresh peas were available, their price would surely ascension. The error here lies in confusing a alter in quantity demanded with a change in demand. Aye, buyers will end up buying fewer peas. But no, they will not demand fewer peas at each price than before; the demand curve does not shift.

Simultaneous Shifts

Equally we take seen, when either the demand or the supply curve shifts, the results are unambiguous; that is, we know what volition happen to both equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity, then long as we know whether demand or supply increased or decreased. Even so, in practice, several events may occur at around the same time that crusade both the demand and supply curves to shift. To figure out what happens to equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity, we must know not only in which management the demand and supply curves have shifted but besides the relative amount by which each curve shifts. Of course, the demand and supply curves could shift in the aforementioned direction or in opposite directions, depending on the specific events causing them to shift.

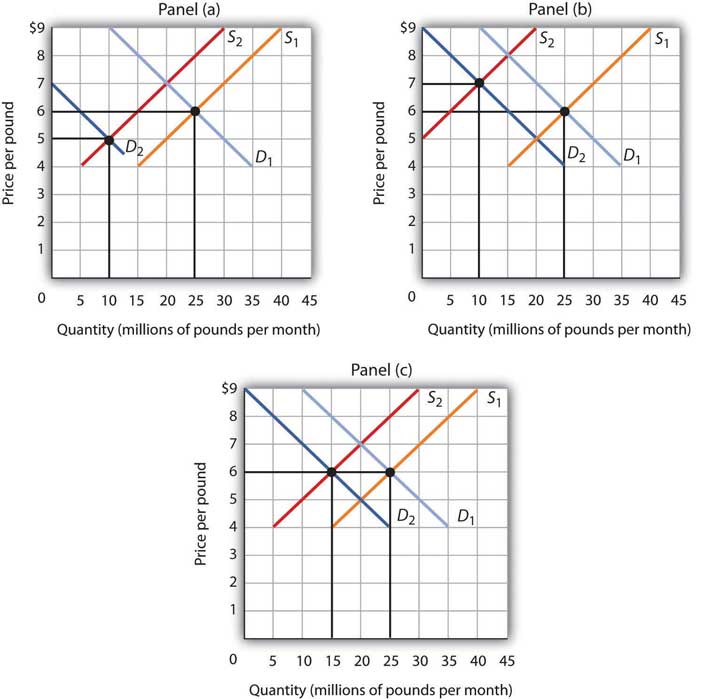

For instance, all iii panels of Figure three.xi "Simultaneous Decreases in Demand and Supply" evidence a subtract in demand for coffee (caused maybe by a decrease in the cost of a substitute good, such every bit tea) and a simultaneous decrease in the supply of coffee (caused maybe by bad weather). Since reductions in demand and supply, considered separately, each cause the equilibrium quantity to fall, the bear on of both curves shifting simultaneously to the left ways that the new equilibrium quantity of coffee is less than the quondam equilibrium quantity. The effect on the equilibrium toll, though, is cryptic. Whether the equilibrium toll is higher, lower, or unchanged depends on the extent to which each bend shifts.

Effigy 3.11 Simultaneous Decreases in Demand and Supply

Both the demand and the supply of java decrease. Since decreases in demand and supply, considered separately, each cause equilibrium quantity to autumn, the touch on of both decreasing simultaneously means that a new equilibrium quantity of coffee must be less than the onetime equilibrium quantity. In Panel (a), the demand curve shifts farther to the left than does the supply bend, and then equilibrium toll falls. In Panel (b), the supply curve shifts farther to the left than does the demand curve, then the equilibrium price rises. In Console (c), both curves shift to the left past the same amount, so equilibrium price stays the same.

If the demand curve shifts farther to the left than does the supply curve, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 3.11 "Simultaneous Decreases in Demand and Supply", and then the equilibrium toll will exist lower than it was before the curves shifted. In this case the new equilibrium price falls from $six per pound to $five per pound. If the shift to the left of the supply curve is greater than that of the demand bend, the equilibrium price will be higher than it was before, as shown in Panel (b). In this example, the new equilibrium toll rises to $7 per pound. In Console (c), since both curves shift to the left by the aforementioned amount, equilibrium price does not modify; it remains $half-dozen per pound.

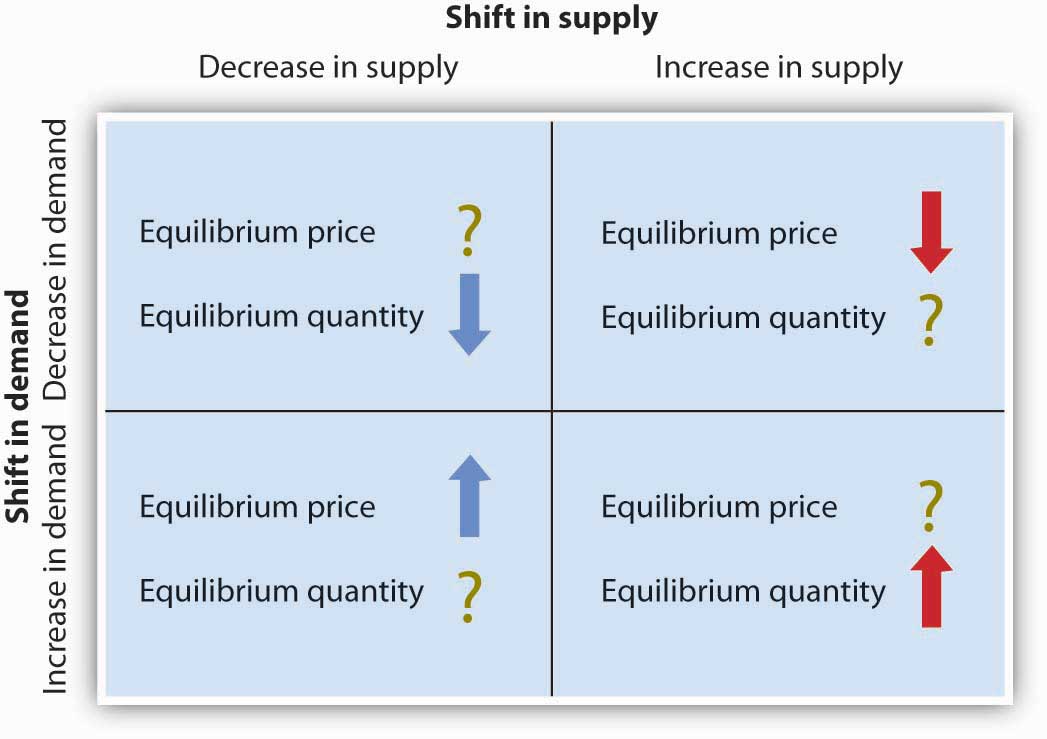

Regardless of the scenario, changes in equilibrium toll and equilibrium quantity resulting from two unlike events need to be considered separately. If both events crusade equilibrium price or quantity to motion in the same direction, then clearly price or quantity can be expected to motion in that management. If one event causes price or quantity to rise while the other causes information technology to autumn, the extent by which each curve shifts is disquisitional to figuring out what happens. Figure iii.12 "Simultaneous Shifts in Demand and Supply" summarizes what may happen to equilibrium price and quantity when demand and supply both shift.

Figure 3.12 Simultaneous Shifts in Demand and Supply

If simultaneous shifts in need and supply cause equilibrium price or quantity to move in the same direction, and so equilibrium price or quantity conspicuously moves in that direction. If the shift in one of the curves causes equilibrium price or quantity to rise while the shift in the other curve causes equilibrium price or quantity to fall, and so the relative corporeality past which each bend shifts is critical to figuring out what happens to that variable.

As demand and supply curves shift, prices suit to maintain a rest between the quantity of a good demanded and the quantity supplied. If prices did non accommodate, this balance could not be maintained.

Observe that the need and supply curves that nosotros take examined in this affiliate have all been drawn as linear. This simplification of the existent world makes the graphs a fleck easier to read without sacrificing the essential point: whether the curves are linear or nonlinear, demand curves are downward sloping and supply curves are generally upward sloping. As circumstances that shift the demand bend or the supply curve alter, nosotros can analyze what will happen to price and what will happen to quantity.

An Overview of Demand and Supply: The Round Flow Model

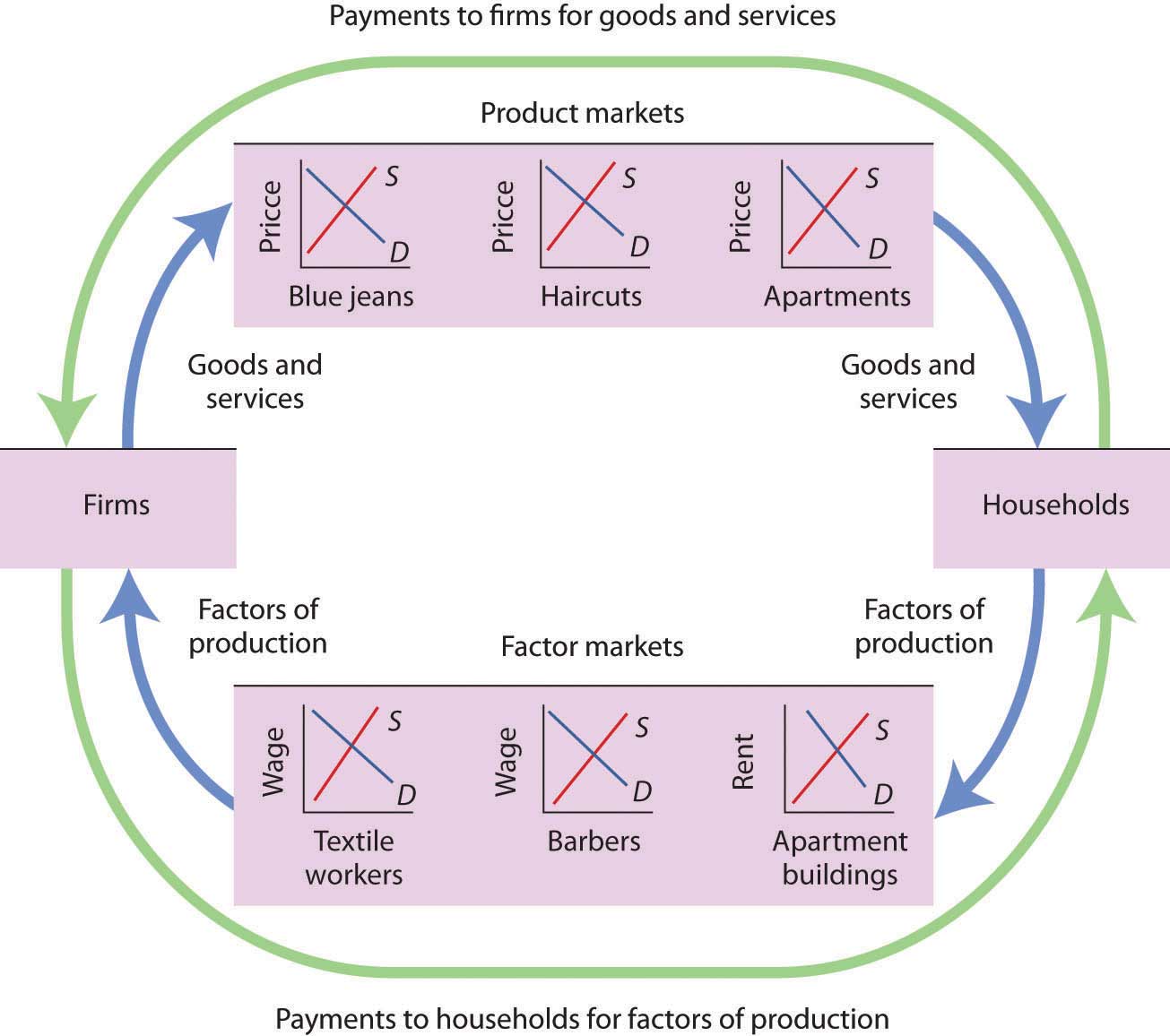

Implicit in the concepts of demand and supply is a constant interaction and adjustment that economists illustrate with the circular flow model. The circular flow model provides a wait at how markets work and how they are related to each other. It shows flows of spending and income through the economy.

A nifty deal of economical activity tin exist thought of as a procedure of commutation between households and firms. Firms supply appurtenances and services to households. Households buy these appurtenances and services from firms. Households supply factors of product—labor, capital letter, and natural resource—that firms require. The payments firms make in exchange for these factors represent the incomes households earn.

The flow of goods and services, factors of production, and the payments they generate is illustrated in Figure three.13 "The Circular Catamenia of Economical Activity". This circular period model of the economy shows the interaction of households and firms as they commutation appurtenances and services and factors of production. For simplicity, the model hither shows simply the private domestic economy; information technology omits the government and foreign sectors.

Figure 3.13 The Round Menstruum of Economical Activeness

This simplified circular flow model shows flows of spending betwixt households and firms through product and factor markets. The inner arrows testify goods and services flowing from firms to households and factors of product flowing from households to firms. The outer flows show the payments for appurtenances, services, and factors of production. These flows, in turn, correspond millions of individual markets for products and factors of production.

The circular catamenia model shows that appurtenances and services that households need are supplied by firms in production markets. The substitution for goods and services is shown in the top half of Effigy 3.13 "The Circular Menses of Economical Activity". The bottom half of the showroom illustrates the exchanges that have place in factor markets. factor markets are markets in which households supply factors of production—labor, upper-case letter, and natural resources—demanded by firms.

Our model is called a circular flow model because households use the income they receive from their supply of factors of production to buy goods and services from firms. Firms, in turn, apply the payments they receive from households to pay for their factors of production.

The demand and supply model developed in this affiliate gives u.s. a bones tool for understanding what is happening in each of these product or factor markets and besides allows united states of america to run across how these markets are interrelated. In Figure 3.13 "The Circular Flow of Economical Activeness", markets for three goods and services that households want—blue jeans, haircuts, and apartments—create demands by firms for fabric workers, barbers, and apartment buildings. The equilibrium of supply and need in each marketplace determines the price and quantity of that item. Moreover, a alter in equilibrium in ane market will affect equilibrium in related markets. For example, an increase in the demand for haircuts would lead to an increase in demand for barbers. Equilibrium price and quantity could ascent in both markets. For some purposes, it volition exist acceptable to just look at a single market, whereas at other times we volition want to look at what happens in related markets as well.

In either case, the model of need and supply is i of the near widely used tools of economic assay. That widespread use is no accident. The model yields results that are, in fact, broadly consistent with what nosotros observe in the marketplace. Your mastery of this model volition pay big dividends in your report of economic science.

Primal Takeaways

- The equilibrium price is the price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. It is determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves.

- A surplus exists if the quantity of a skilful or service supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the current cost; it causes downward pressure on price. A shortage exists if the quantity of a adept or service demanded exceeds the quantity supplied at the current price; it causes upwards pressure on price.

- An increment in need, all other things unchanged, will cause the equilibrium price to rise; quantity supplied will increment. A decrease in demand will crusade the equilibrium price to fall; quantity supplied will decrease.

- An increment in supply, all other things unchanged, will crusade the equilibrium price to fall; quantity demanded will increase. A decrease in supply will cause the equilibrium price to ascension; quantity demanded will decrease.

- To make up one's mind what happens to equilibrium price and equilibrium quantity when both the supply and need curves shift, yous must know in which management each of the curves shifts and the extent to which each curve shifts.

- The circular flow model provides an overview of need and supply in product and factor markets and suggests how these markets are linked to 1 another.

Attempt It!

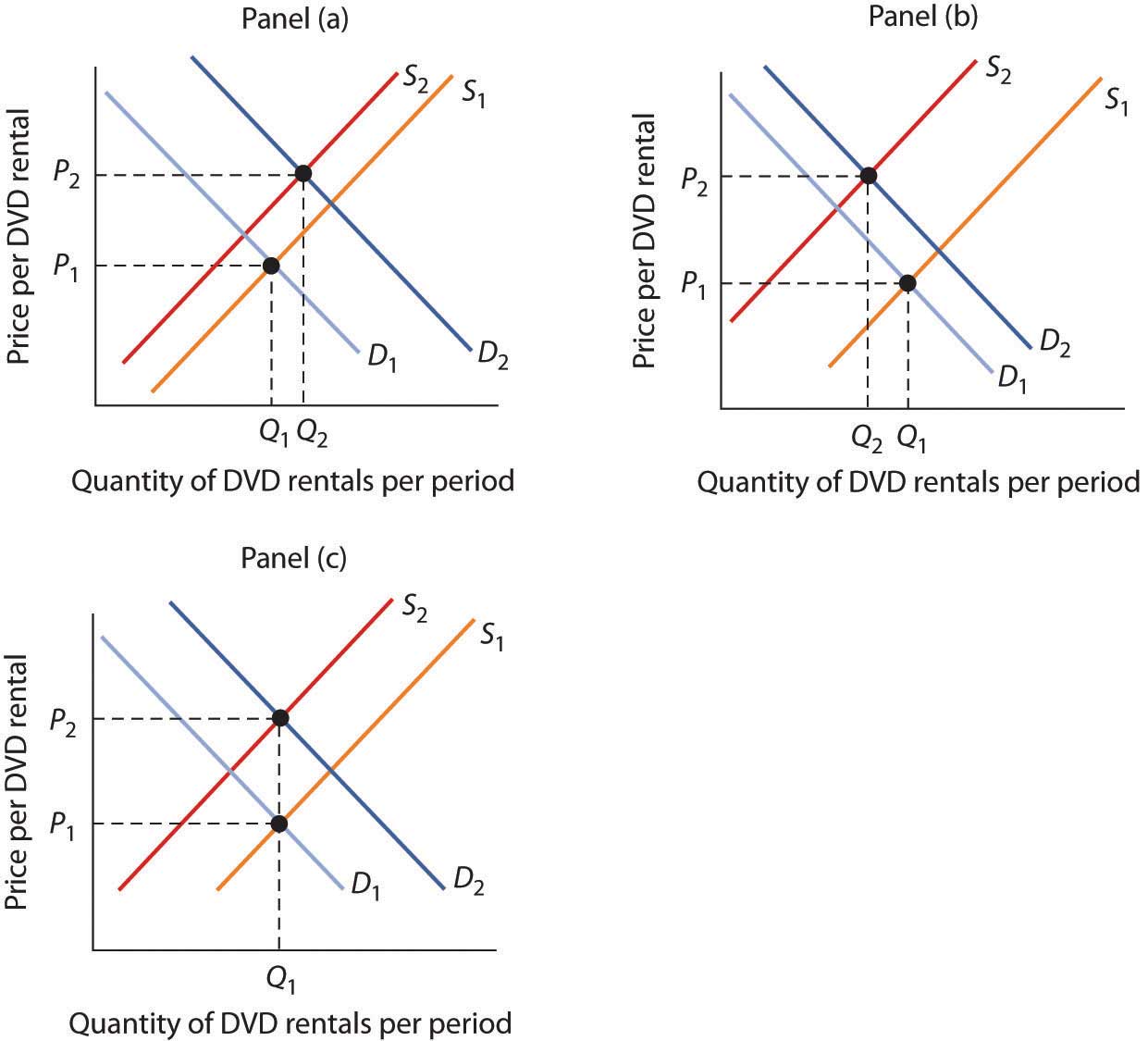

What happens to the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals if the price of movie theatre tickets increases and wages paid to DVD rental store clerks increase, all other things unchanged? Be certain to prove all possible scenarios, as was washed in Figure 3.eleven "Simultaneous Decreases in Demand and Supply". Over again, yous do not need actual numbers to arrive at an answer. But focus on the general position of the bend(southward) before and later on events occurred.

Case in Point: Need, Supply, and Obesity

Why are so many Americans fatty? Put so crudely, the question may seem rude, only, indeed, the number of obese Americans has increased by more than 50% over the last generation, and obesity may at present be the nation's number one health trouble. According to Sturm Roland in a recent RAND Corporation study, "Obesity appears to accept a stronger association with the occurrence of chronic medical conditions, reduced physical health-related quality of life and increased health intendance and medication expenditures than smoking or trouble drinking."

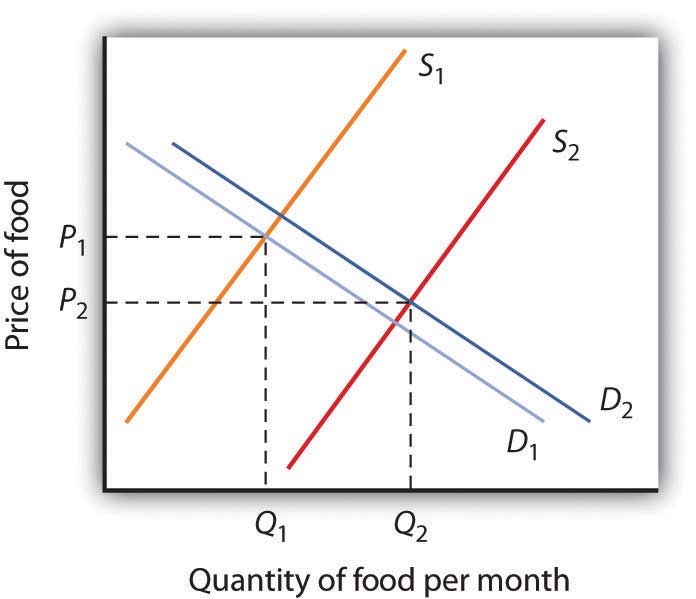

Many explanations of rising obesity advise higher demand for food. What more apt picture of our sedentary life fashion is there than spending the afternoon watching a ballgame on Television set, while eating chips and salsa, followed past a dinner of a lavishly topped, have-out pizza? Higher income has too undoubtedly contributed to a rightward shift in the demand curve for food. Plus, whatsoever additional food intake translates into more weight increase because we spend and so few calories preparing information technology, either straight or in the process of earning the income to purchase it. A study by economists Darius Lakdawalla and Tomas Philipson suggests that about 60% of the recent growth in weight may exist explained in this fashion—that is, need has shifted to the correct, leading to an increment in the equilibrium quantity of food consumed and, given our less strenuous life styles, even more weight gain than can exist explained simply by the increased amount we are eating.

What accounts for the remaining 40% of the weight gain? Lakdawalla and Philipson farther reason that a rightward shift in demand would past itself lead to an increase in the quantity of food as well as an increase in the price of nutrient. The problem they have with this caption is that over the post-World War 2 period, the relative price of nutrient has declined by an boilerplate of 0.2 percentage points per twelvemonth. They explain the fall in the price of food by arguing that agronomical innovation has led to a substantial rightward shift in the supply bend of nutrient. As shown, lower nutrient prices and a college equilibrium quantity of nutrient have resulted from simultaneous rightward shifts in need and supply and that the rightward shift in the supply of food from S one to S two has been substantially larger than the rightward shift in the demand curve from D ane to D 2.

Sources: Roland, Sturm, "The Furnishings of Obesity, Smoking, and Problem Drinking on Chronic Medical Issues and Health Care Costs," Health Affairs, 2002; 21(two): 245–253. Lakdawalla, Darius and Tomas Philipson, "The Growth of Obesity and Technological Change: A Theoretical and Empirical Examination," National Bureau of Economical Research Working Paper no. w8946, May 2002.

Reply to Try Information technology! Trouble

An increment in the cost of motion-picture show theater tickets (a substitute for DVD rentals) will cause the need curve for DVD rentals to shift to the right. An increment in the wages paid to DVD rental store clerks (an increase in the price of a factor of production) shifts the supply curve to the left. Each event taken separately causes equilibrium price to rise. Whether equilibrium quantity will be college or lower depends on which curve shifted more.

If the need curve shifted more, then the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals will ascension [Console (a)].

If the supply curve shifted more than, then the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals will fall [Console (b)].

If the curves shifted by the aforementioned amount, and then the equilibrium quantity of DVD rentals would not change [Console (c)].

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/macroeconomics/chapter/3-3-demand-supply-and-equilibrium/

0 Response to "what caused cotton and tobacco prices to fall 8-6.2"

Postar um comentário